'Refracting Histories' Exhibit Challenges Art Legacies

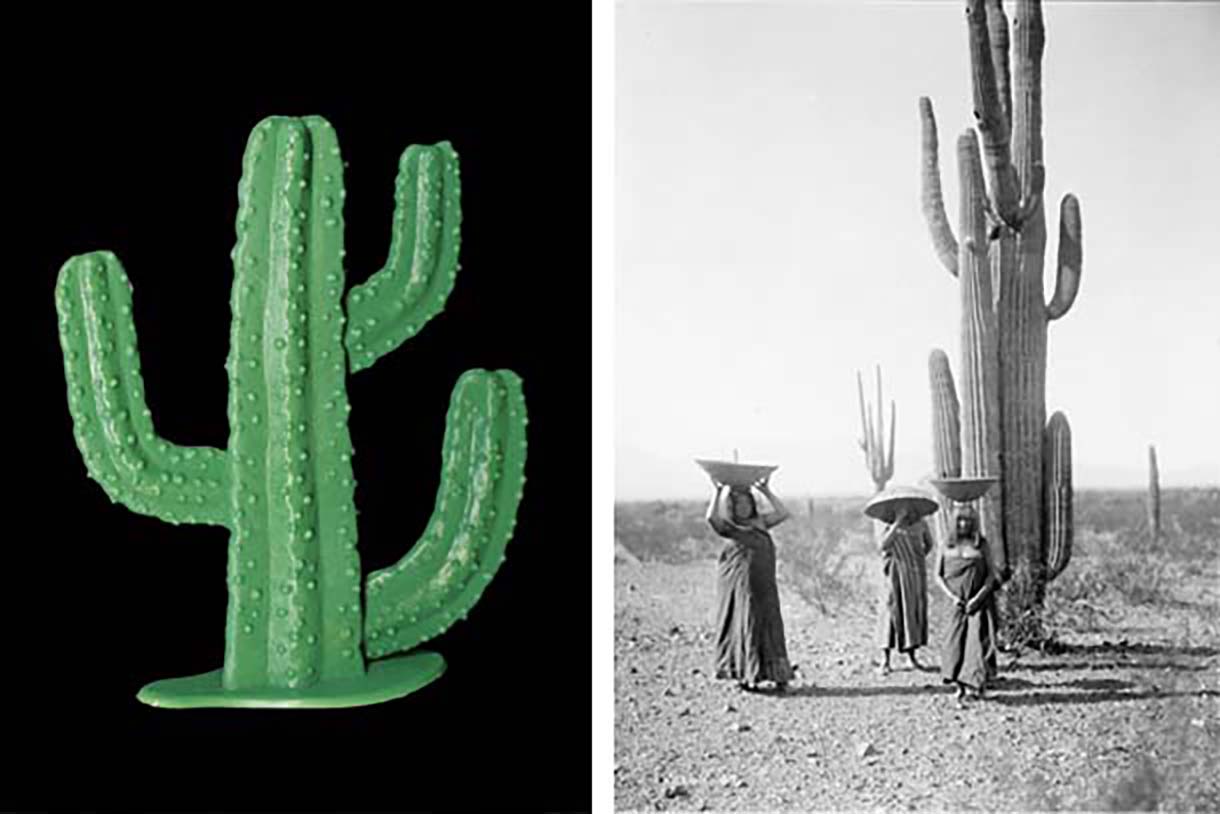

Left to right: Tom Jones, "A Maricopa Landscape," from "The North American Landscape" series, 2013; Edward S. Curtis, "Maricopa Women Gathering Fruit from Saguaro Cacti," from "The North American Indian," 1907. Note: Curtis’s photo shown for reference only. It is not in the MoCP exhibition or collection.

Left to right: Tom Jones, "A Maricopa Landscape," from "The North American Landscape" series, 2013; Edward S. Curtis, "Maricopa Women Gathering Fruit from Saguaro Cacti," from "The North American Indian," 1907. Note: Curtis’s photo shown for reference only. It is not in the MoCP exhibition or collection.Columbia College Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) currently features the exhibit Refracting Histories, which will be on display through April 2. In the exhibit, eight artists look critically at the traditional canon within the history of photography. Each artist challenges, probes, or deconstructs well-known art historical legacies, revealing the contributions of overlooked makers as well as pervasive discrimination that maintains the status quo.

Exhibiting artists include Tarrah Krajnak, Aaron Turner, Sonja Thomsen, Colleen Keihm, Tom Jones, Nona Faustine, Kelli Connell, and Natalie Krick.

Kristin Taylor, curator of Academic Programs and Collections at the MoCP, recently participated in a Q&A about the exhibit.

In what ways does this exhibit challenge the traditional canon of photography?

I curated this exhibition with the MoCP Deputy Director and Chief Curator Karen Irvine. We invited artists who are interested in changing the direction of how we look at art history. Each artist, in their own way, reveals multilayered, often misplaced stories that exist alongside more dominant narratives. For example, Tarrah Krajnak uses her own body to re-create images Edward Weston made of nude women in the 1920s and 1930s.

Weston is highly regarded as a modernist master, but Krajnak considers the creative role each model played in making the images. In her interpretations, you can see Krajnak holding the camera shutter release in her hand and looking directly at the camera, as opposed to Weson’s images that often cropped off the head of the figure. She asks us to consider if Weston was the sole author of these works. More broadly, she is questioning who has helped people achieve fame and recognition in this field—and what is left out of this process of adoration.

Another artist, Aaron Turner presents multiple photographic translations of Frederick Douglass. Most people know Douglass as the US abolitionist and statesman, but many do not learn that he was also the most photographed man of the nineteenth century and one of the first critical theorists of photography. Turner appropriates and creates multiples of an early portrait of Douglass to reflect on his under-recognized and prescient views on the photographic image, and to amplify his important contributions to the history of photography.

Why was this cross-examination needed?

When we look more critically at the values placed on some artists over others, we can see how our narrow canons — which almost always prioritize the work of white cis men — have a ripple effect on where we place values, both culturally but also in the market of collecting and displaying art. If we think of new possibilities of radical inclusion, we can disrupt conventions of good or bad, and move toward the possibility of a more equitable and democratic art historical narrative.

What is unique about this collection and/or the photographers featured?

There are site-specific installations throughout the exhibition — one by Sonja Thomsen and two by Natalie Krick and Kelli Connell (who also is professor and graduate program director of Columbia's Photography department). Sonja Thomsen created an immersive space in the MoCP stairwell that is a tribute to Lucia Moholy, whose career was overshadowed by her once husband, Bauhaus educator László Moholy-Nagy. Thomsen works with reproductions of Moholy’s photographs, cropping sections to emphasize imagery of hands across different generations to underscore unacknowledged labor and care provided by women. She places images within varying levels of light, which fluctuate in the installation depending on where one stands. Looking up, a mobile titled and manner of our collaboration (2022) recalls an apostrophe, the punctuation of possession. Thomsen invites us to reconstruct Moholy’s fragmented legacy and to question our modes of access to information by animating the link between the known and the unknown.

Kelli Connell and Natalie Krick took over two areas for their project, titled O Man! The series places a contemporary feminist lens on the work of Edward Steichen and his position as the curator of the famous exhibition The Family of Man, presented in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Connell and Krick bring Steichen’s work into a current dialogue about power, with a humor at once whimsical and deliberate. They also include text panels throughout their installations that employ techniques typically seen in redacted poetry. By removing words from original text passages found in The Family of Man catalog, Connell and Krick isolate and emphasize recurring language that, viewed with a 2022 sensibility, seems explicitly gendered. One text passage reads, “all things relative,” reminding us that what we teach about our histories is not objective, and what we know about the history of art is often traceable to critics who deemed certain works or artists more intrinsically valuable than others.

How do you hope visitors will be transformed by seeing this exhibit?

We hope that people will engage with this exhibition on many levels. For people who visit who have taken History of Photography courses, we hope they will consider expanding their own research into what is not taught. It’s not to say that people like Steichen and Weston did not make significant contributions to the history of the medium—they certainly did. But what else can we find? If the “masters of photography” are not speaking to you, dig deeper to find works that do.

We also hope people will think broadly about how we access information. One artist in the exhibition, Nona Faustine, considers how photographs shape larger national narratives. In her long-term project titled White Shoes, she makes self-portraits in locations around New York that have undertaught — or untaught —histories of enslavement. Although there are many layers in Faustine’s work about the history of photography and visual culture, she uses white shoes to represent overarching whitewashed patriarchal histories.

What has the response been to the exhibit so far?

Very positive! Although the exhibition tackles some heavy subject matter, there is also a good amount of whimsy and humor. For example, Columbia College Chicago Alum Tom Jones satirically interprets images from Edward Curtis’s iconic North American Indian book of 1907, which portrayed a stylized version of Native American people from an outsider perspective. Jones, who is a member of the Ho-Chunk tribe, creates images of plastic toys that match trees found in the backgrounds of Curtis’s images. Each image is titled with the name of the tribe belonging to the region where a specific tree grows, revealing the many Indigenous groups and identities that have been flattened into one idea of “Indian-ness” over time.

His work is a great example of the overall mood of the exhibition. And he will be here to speak on Wednesday, March 8 at 6 p.m. at the Ferguson lecture hall! We hope people interested in this exhibition will attend his lecture.

Watch these videos and learn more about Refracting Histories: